Truth and Beauty in Houston

Not to be missed! Audubon’s Birds Of America At The Houston Museum Of Natural Sciences

Once upon a time, Art and Science were more than betrothed: They were married. Their goals were congruent: The discovery of truth. In Art, beauty; in Science, knowledge. The paintings of John James Audubon (1785-1851), outdoorsman, naturalist, painter and creator of The Birds of America and The Quadrupeds of North America, are its children.

The Houston (Texas, USA) Museum of Natural Sciences currently exhibits1 Audubon’s ornithological illustrations on loan from the Scottish National Museum until September 1, 2025, including:

75 large paper color prints2 and several engraved plates upon which prints were inked;

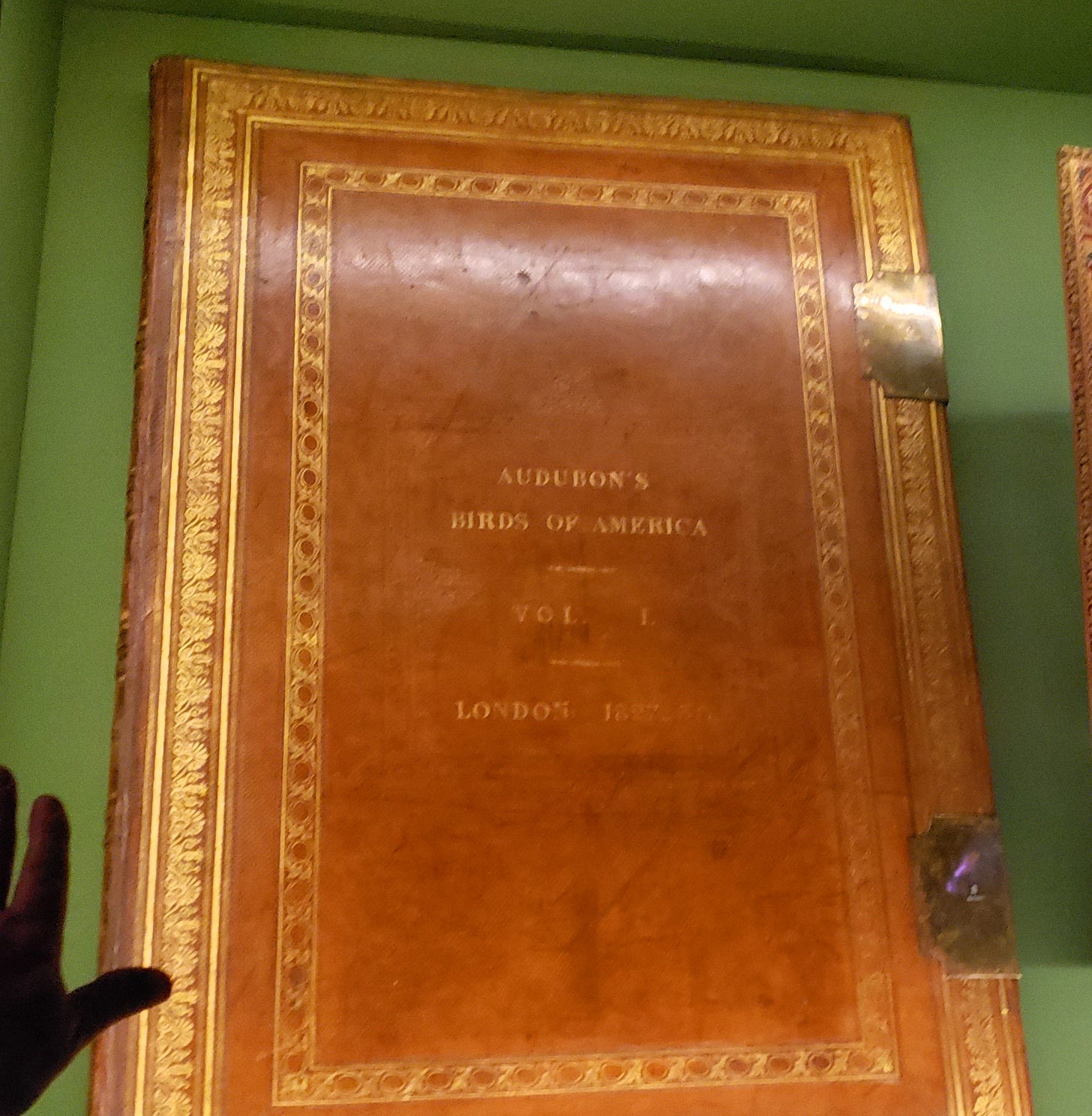

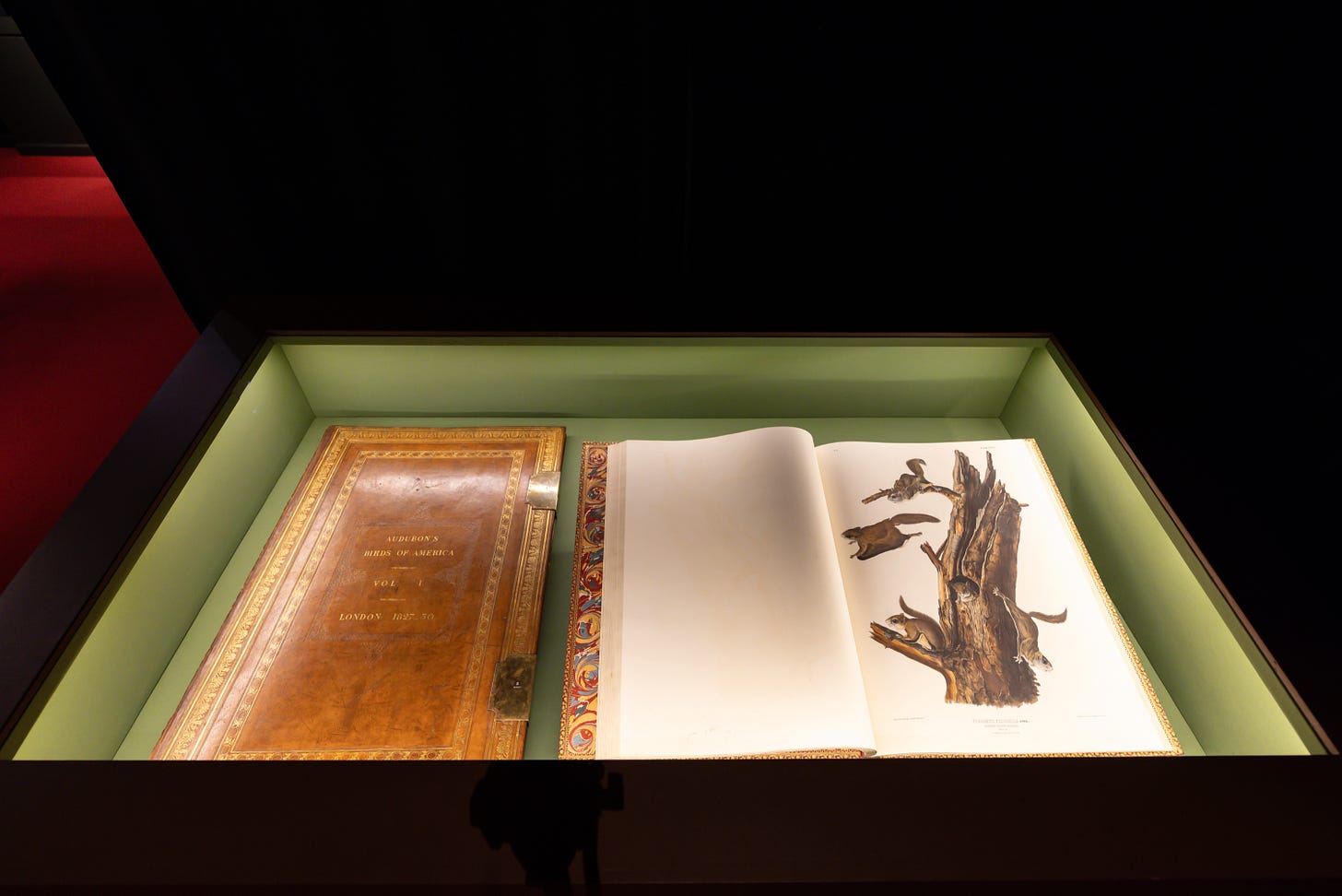

The famed and elusive gilded leather folio of the double-elephant prints, as tall as a 3 year old and as wide as your arm (39½ H x 26¼ W), and other later bound editions;

An inlaid map-desk for their display the size of a Mini-Cooper; a letter in Audubon’s hand to Scottish scholar, George Jardine; a rival illustrator’s copy of a print, which led to a lawsuit in copyright infringement; and other ephemera.

An auto-didact, Audubon’s eye for talent was as unerringly keen as his artistry, hiring William Lizars in Edinburgh and the Robert Havells (Sr. and Jr.) in London as the engravers and inkers who produced the prints from Audubon’s original watercolors.3 Each print is exquisite. Audubon’s subjects, birds at rest, nesting, in the hunt or in flight, are set against natural backdrops that enhance the viewer’s delight.

The prints are beautifully matted, framed and hanged. Illuminated by the highest aesthetic comprehension of artificial light, typical of this museum, as with Houston ballet and opera, an otherwise ordinary carpeted hall becomes a hushed cavern of luxuriant beauty.

THE FOLIOS

Between 1826 and 1860, Audubon (and after his death in 1851, Roe Lockwood) published three editions of his The Birds of America.4 Of the first edition (double elephant folio, London, 1826-1838), perhaps 190 complete sets of 435 prints, sold in 87 five-print parts over many years, were issued. 120 complete sets remain today in institutional collections and the occasional private library.5 Single prints can be found on the market today, but bound elephant folio volumes are rare. Audubon did not bind them and it is unknown how many subscribers did.

Most stunning of all, over and above the folio which one expects to see, is the enormous map case, purpose-built to house a complete bound set. For whom was the map case made? Who made it and where? Of what woods? The exhibit doesn’t say.

AUDUBON’S ACHIEVEMENTS AND THE TENOR OF HIS TIMES

Audubon’s achievements sprang from a fertile soil: Ideas as common and as central to inquiry then, as they are rare and tangential to those who claim to be artists and intellectuals today. The marriage of Art and Science was sundered long ago. The pursuit of truth to which their practitioners once mutually devoted their lives was abandoned.

John Ruskin devoted Modern Painters (London, 1843-60) to the principle that the “truths of nature” can be and must be depicted faithfully by artistic means. The 19th century naturalist’s knowledge of the scientific truths of nature relied upon the aesthetic fidelity of the artist’s observations of nature as much as the naturalist’s. To be discovered, truth must exist: If there is no truth, nothing truthful can be discovered. 19th century naturalists and artists agreed that truth is, and that man can readily discover, comprehend, demonstrate and communicate it.

Faith and confidence in the discovery of truth, covalent with beauty, and man’s capacity for its attainment, recognition and adoption, pervaded the consciousness of the 19th century scholar, artist, scientist, composer, poet, and in fact, every literate adult’s consciousness. As Keats in his concluding couplet to Ode to a Grecian Urn (1819) wrote:

Audubon’s prints demonstrate that his conception of the natural world was congruent with this ideal. His watercolors, the result of thousands of hours observing birds at rest, nesting, in the hunt and in flight in their American habitats refine natural complexity and the chaos of animalia into a seeming simplicity of beauteous form that was -- and is still today -- true to nature.

“Every bird has its own character, and every picture tells its own story, and is full of life and interest.”6

Each print is immediate, fresh, forthright and simple, much like the person of Audubon himself. Sir Walter Scott met an awed Audubon on Jan. 22, 1827:

“He is an American by naturalization, a Frenchman by birth, but less of a Frenchman than I have ever seen, -- no dash, no glimmer or shine about him, but great simplicity of manners and behavior; slight in person and plainly dressed; wears long hair which time has not tinged; his countenance acute, handsome and interesting, but still simplicity is the predominant character.”7

Scott and Audubon met in Scotland, where Audubon had traveled in search of subscribers. A bevy of literate individuals, intrigued by the freedom of the wild American frontier, its abundant prospects for scientific discovery, the liberty of its adventurous people and their developing markets, welcomed him there.

Sir Edward Forbes (1815-1854) wrote of his life at university in Edinburgh in 1833-34:

The man who has gazed upon and felt the worthy delineation of a glorious landscape…never forgets the genial, wholesome, glow of admiration that pervades his spirit at the time. How much more must he feel this ennobling sensation when he gazes on the reality of majestic landscape? And if, with all this precious accumulation of the vast and beautiful, there be combined that which is admirable in the minute—if nature, in her smallest elements, be prolific in objects of study and reflection, it is not to be wondered at that this University has been a hot-bed of naturalists, and that their philosophy has been one catholic in essence and far-extending in its range.”8 [Emphasis, mine.]

The “Scottish Enlightenment” was a century of vibrant discovery, invention and scholarly disputation, whose progenitors assumed that truth, beauty and the plenitude of God9 were ripe for discovery. A proliferation of writings on human reason, liberty, markets and geological time established theoretical edifices of civilization thereafter disseminated widely. Inventions of practical application resulted: Macadamisation, the condensing steam engine and shale oil extraction. Scotland was widely considered to be the most literate nation in Europe. It was in Scotland that Audubon found many people like-minded to him who admired his work and his person.

A DENIGRATION OF AUDUBON THE MAN

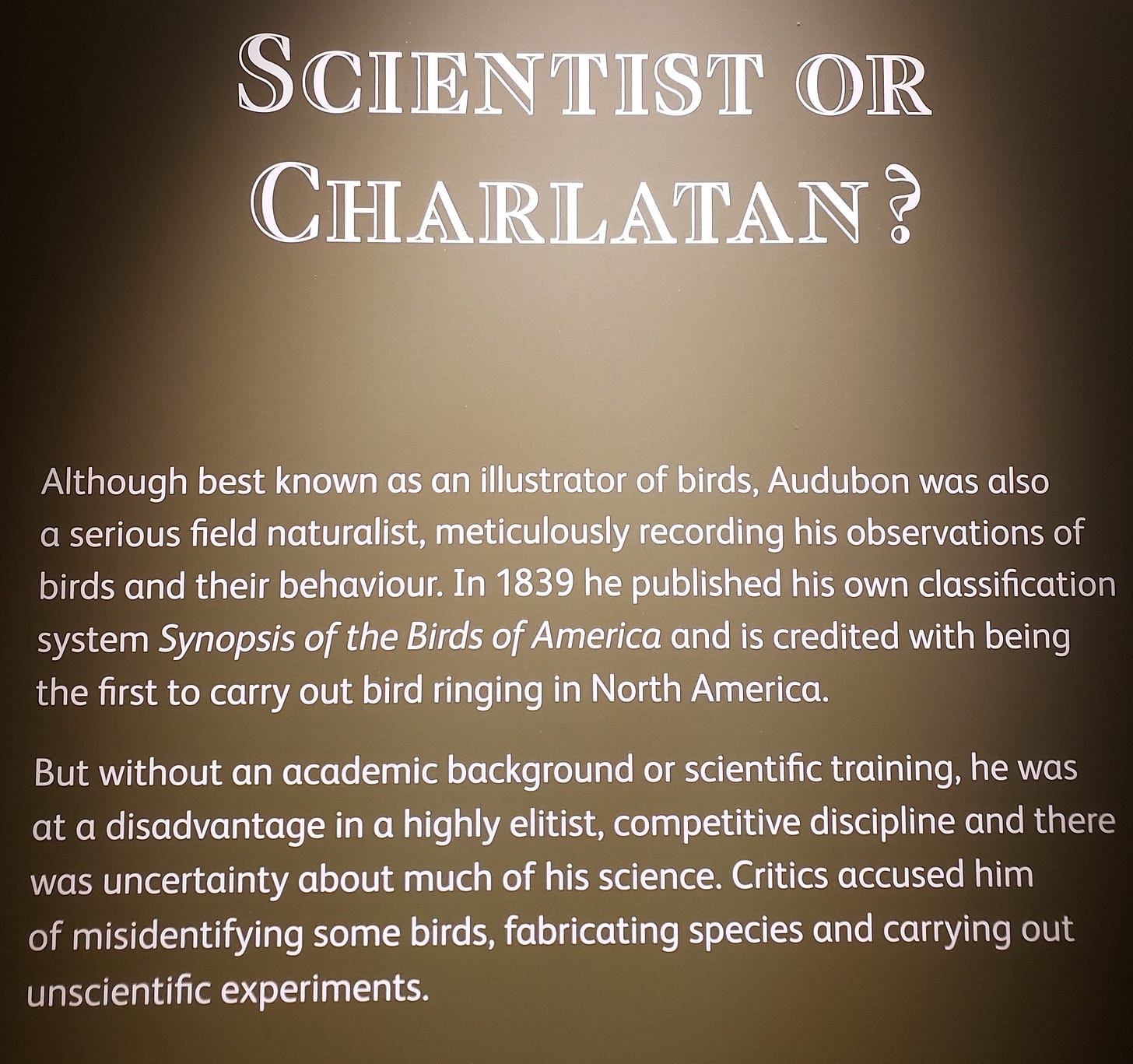

This sensational exhibit is a demonstration of the 19th century alliance of art and science. Truth and beauty – Audubon’s prints -- are luxuriantly present and captivatingly displayed. Sadly, the featured theme of the curation is an outrage: The denigration of the man whose work is featured.

Witness the placards that greet patrons to the exhibit.

I stood before this placard near the entryway, puzzled. If “it is difficult to know the truth” about Audubon the man because his life “is full of contradiction and controversy,” how can anything be said about him with confidence? Isn’t the study of history the clarification of past events and people, and not mere accusation? Sir Roger Scruton came to mind: “A writer who says that there are no truths, or that all truth is ‘merely relative,’ is asking you not to believe him. So don’t.”10

Before the museum-goer sees even a single Audubon print, the curator has leveled a broadside to bias him: A story-line fashioned to leave the exhibit-goer with an unsavory taste in the mouth about Audubon the man. In so doing, the curator defiles by misdirection the stupendous and unique work Audubon achieved.

Digesting the totality of the placard text and the films displayed, as I discuss below -- if the curator is to be believed -- Audubon may, in fact, have been mendacious, difficult and complicated, a bankrupt, a con, a killer (of wildlife) and a slave owner! During his lifetime, Audubon was defamed (see below), but he was alive to defend himself. Any historical thesis must be proven with evidence -- in an exhibit no less than any scholarly work – especially when the man accused is unavailable to defend himself. But nowhere in this exhibit is there any substantiation for these accusations.

“Scientist or Charlatan” is a false dichotomy because it requires the museum-goer to choose either of two mistaken perceptions. First, the man was an artist whose subject was nature, as were the illustrator-naturalists Joseph Banks, Thomas Bewick, Marianne North and Pierre-Joseph Redouté. Were they “scientists or charlatans,” too? Does the curator wish to imply that an artist who depicts the natural world, now exclusively the province of science. is a charlatan? Can a charlatan create 485 exquisite works of art? And who claimed that Audubon was a charlatan, if not the curator? Perhaps Audubon’s competitors: Alexander Wilson, George Ord and Charles Waterton.

Alexander Wilson (1766-1813) was a Scottish illustrator of nature. An Edinburgh court imprisoned him for non-payment of a fine, issuing in libel, and in 1794, he emigrated to the United States. Prospecting for patrons for his own illustrations, he chanced upon Audubon in Louisville, Kentucky in 1810. Audubon wrote of this meeting 21 years later:

He opened his books, explained the nature of his occupations, and requested my patronage. I felt surprised and gratified at the sight of his volumes, turned over a few of the plates, and had already taken my pen to write my name in his favour, when my partner rather abruptly said to me in French: 'My dear Audubon, what induces you to subscribe to this work! Your drawings are certainly far better; and again, you must know as much of the habits of American birds as this gentleman.' Whether Mr. Wilson understood French or not, or if the suddenness with which I paused disappointed him, I cannot tell; but I clearly perceived he was not pleased. Vanity, and the encomiums of my friend, prevented me from subscribing. Mr. Wilson asked me if I had many drawings of birds, I rose, took down a large portfolio, laid it on the table, and showed him as I would show you, kind reader, or any other person fond of such subjects, the whole of the contents, with the same patience, with which he had showed me his own engravings. His surprise appeared great, as he told me he had never had the most distant idea that any other individual than himself had been engaged in forming such a collection. He asked me if it was my intention to publish, and when I answered in the negative, his surprise seemed to increase. And, truly, such was not my intention; for, until long after, when I met the Prince of Musignano in Philadelphia, I had not the least idea of presenting the fruits of my labours to the world. Mr. Wilson now examined my drawings with care, asked if I should have any objection to lending him a few during his stay, to which I replied that I had none.11

Wilson’s extant letters do not appear to mention a meeting with Audubon. But George Ord (1781-1863), whom Wilson made executor of his estate upon his death in 1813, was himself also a naturalist-illustrator with a competing book to Audubon’s. Ord seems to have been bitterly envious of Audubon and, in 1824, apparently blackballed Audubon’s nomination to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Ord claimed to possess the journal Wilson kept of his American travels in which Wilson is supposed to have written on March 20, 1810, that he went out shooting with “no naturalists to keep me company.”12 Ord’s implication was that Audubon had falsified his biographical account of the 1810 meeting. Wilson’s journal, if it ever existed, was not found in Ord’s estate upon his death and may never have existed. Audubon described Ord privately as “the venomous tallow chandler of Philadelphia,”13 a diminutive reference to his family’s profession.

Englishman Charles Waterton (1782-1865), yet another competing nature illustrator, had also met Audubon in America. Charles Darwin heard Audubon sneer “unjustly” at Waterton during an 1827 Wernerian Society lecture.14 Waterton ridiculed Audubon’s 1832 Ornithological Biography (quoted above) as “AN ARRANT YANKEE DOODLE HOAX”15 (all in caps in the original). Does any of this make Audubon a charlatan? By no stretch of the imagination. These men were competitors in the hunt for a scattering of wealthy patrons.

Why, in any case, choose to feature vituperative accusation of the artist’s character side by side with the beauteous expressions of his creative intelligence? Why did the curator not defend him? There is something cowardly in a libel against the dead, especially when praise is readily found, here, a Scotsman who knew Audubon asserting his universal esteem:

He is the greatest artist in his own walk that ever lived, and cannot fail to reap the reward of his genius and perseverence and adventurous zeal in his own beautiful branch of natural history both in fame and fortune. The Man himself whom I have had the pleasure of frequently meeting – is just what you would expect from his works – full of fine enthusiasm and intelligence…a perfect gentleman and esteemed by all who know him for the simplicity and frankness of his nature.”16

Did his illegitimacy render him more or less brilliant an artist? As to “failed businessman and bankrupt,” what of it? Are exhibit-goers to revile Audubon as a bankrupt (the exhibit doesn’t offer proof by way of a bankruptcy filing) when 517,308 cases of bankruptcy were filed in 2024,17 to which stigma is no longer attributed, and bankrupts haven’t been imprisoned for debt since 1839?18 How many other men living by their wits in the pre-Civil War American wilderness failed?

As to “self-promotion” (see below), it is as if the Scottish literati contemporaries who were enamored with his work and helped to promote him never existed. It is more determinative of character that Audubon persisted – over 30 years – to achieve the goals of his lifetime despite of the hardships he endured. The proffered dichotomy – successful fundraiser or bankrupt – is specious.

“Claimed” implies mendacity, as if Audubon lied about his method, when in truth he was a supreme artist of expertise and discrimination in depicting the natural world. The exhibit offers nothing substantive in regards to Audubon’s methodology. I will let Audubon himself respond:

“My drawings have all been made after individuals fresh killed, mostly by myself, and put up before me by means of wires, &c. in the precise attitude represented, and copied with a closeness of measurement that I hope will always correspond with nature when brought into contact… I have never drawn from a stuffed specimen. My reason for this has been, that I discovered when in museums, where large collections of that kind are to be met with, that the persons generally employed for the purpose of mounting them possessed no further talents than that of filling the skins, until plumply formed, and adorning them with eyes and legs generally from their own fancy.”19

If any quote were directly relevant to the Audobon’s methods, it is this one; a contradiction of the mendacity the curator insinuates.

THE FILMS

Two films were worth watching, one being an informative demonstration of the engraving and inking process and another of Audubon’s life in Edinburgh, produced by the Scottish National Museum who originated the exhibit. But even here the scholarship of the latter was perfunctory. It features a speaking Audubon. The (perhaps Scottish) voice actor delivered his lines in nearly standard mid-Atlantic American, peppered with a single, but repeated affectation: “The” was pronounced “zuh.” I found myself asking if Audubon was German. I turned to my brother, James, who knows many German- and French-born people, to hear him echo my question: “Audubon was German?” But, no, the voicing was wrong. [In the clip below, you will hear background noise as well as the voiceover.]

In 1843, Andrew Coates, a Scotsman, visited Audubon in Minnie’s Landing, now part of the Audubon Park district in New York City, wrote:

“He had a strong French accent – so strong, indeed, that one would have imagined he had newly left the country in which he had spent his early years…”20

Disquieted, I took comfort in the beauty that surrounded us. The curators, however, would not let it rest. Three films set my teeth on edge. (I’ve transcribed the quotations which follow from the films.)

Peter Logan, biographer:

“It’s a magnificent artistic compendium and will forever stand as a tribute to ornithology and natural history, and likely will never be equaled…In the last few years, he’s been condemned because he owned slaves, 21 a fact that biographers have known and revealed for over a century. It was an abhorrent practice. There’s no getting around that – America’s original sin.”

Audubon owned slaves. Revile him!

Not only is Audobon supposed to be bad: America is bad! Does this “original sin” stain the American abolitionists as well, or was that just “an arrant Yankee Doodle hoax?”

What’s the next step, after destroying his reputation? Destroying his art. That would seem to be the logical conclusion of their illogic. The evil fruit of Audubon’s abject sinfulness must be erased, just as the Taliban in 2001 dynamited the Buddhas of Bamiyan.

Dr. J. Drew Latham (Clemson Univ.):

“John James Audubon pushes us into that place…of having to consider genius and maybe contributions to society, but also humanity and detractions from society. And so he stands as a model for those who would see him as some sort of bird god and those of us who have ancestors who were in that place of being owned as chattel, enslaved, and to see that person as less than worthy, much less than worthy of any sort of celebration.”

This word salad – “bird god?” -- is trotted out as best of breed. Go on, guess ornithologist Dr. Latham’s skin color! It was not enough to have a white male (Mr. Logan) pontificate on camera his irrelevant apologia of collective racial guilt for the purported actions of a dead man. The curator had anticipated that you might praise Audubon, and so, to avoid that possibility, brought in Big Bertha: A black ornithologist. Dr. Mumbles unctuously speechifies from on his pedestal high his utter condemnation of Audubon. This is to shut you up. Dr. Mumbles’s people have suffered, so you can’t criticize him. Touché!

I did NOT make this up. Watch:

What peccadilloes might a scholar of the next century find in the lives of the people involved in the production of this exhibit, do you think? Matthew 7:1-3 (KJV) comes to mind.

Judge not, that ye be not judged. For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again. And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother's eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?

But, wait! “Climate change” is to be blamed on Audobon, too.

Dr. Latham:

“…sadly, now we have this understanding of billions of birds having disappeared…over the last fifty years…and if we are to continue on this current trend of decline in 80 years, sadly. We may be talking about the last of their kind.”

Peter Logan:

“We have the ability to reduce carbon emissions and we owe it to the generations that follow…to do everything in our power to act now.”

The dogma of “diversity” requires a woman for “authentic inclusiveness.” Couldn’t they have found an “Asian” woman? Nonetheless, their white woman talking head fills out the bill of attainder to the dotted DEI.

Roberta JM Olson (Curator of Drawings, New York Historical Society Museum & Library):

“What it means is that we all have to take action, not in the future, but today, if anything is able to stop what generations have put in motion. And it is extraordinarily frightening with climate change…it would require unbelievable international cooperation…it is dire, and I think that everyone needs to get on board.”

This is Chicken Little Chiliasm!22 I laughed out loud: The hoax of man-made climate change, America’s most abundant cash crop, has made its way into a Museum of Science. Everyone needs to get on board “the gravy train.” But my laugh vanished in the next moment. To bring about the net-zero utopia these people dream of, governments must compel the compliance of 6 billion people. Hasn’t humanity suffered enough from the destruction caused by tyrannical mandates?

AN EXHIBIT NOT TO BE MISSED

I can not recommend this exhibit highly enough. Audubon’s artistic achievements represent a pinnacle of aesthetic consciousness. Even one visit enriches and edifies.

Sadly, the curator of this exhibit holds the man who created 485 masterpieces at arm’s length like a full diaper. Caustic contempt is common today among artists and intellectuals – more often hacks and pseudo-intellectuals – whose animus engenders the destruction of the nourishing ideas they were traditionally supposed to nurture. The curation, however, reveals that the academy today, a descendant of the Scottish Enlightenment, is poisonous fruit that has fallen far from the tree.

Besides, it is a simplistic reduction of a man’s life, which is an ever expanding, ever deepening globe, its complexity nuanced by detail in the context of the time in which he lives, to be fit squarely into tightly predetermined ideological boxes. In fact, were any of these accusations about Audubon the man true, none of them would be relevant in the least to an appreciation of Audubon’s work. It is not the man who is important, but what he has achieved.

Imagine if, just before the curtain rose on Parsifal (https://birthofvenus.substack.com/p/the-globalization-of-parsifal), the house announced, “Out of respect to your neighbors, please shut off your cellphone, so that they may hear without interruption the extraordinary music of its loathsome, self-obsessed, manic depressive, money-grubbing leech of a Jew-hating composer.” This exhibit has done precisely that.

Audubon and his contemporaries are dead. But they knew that creation is shot through with truth and the beauty. What they discovered – which they first had to posit -- is inextinguishable. That is why, even today, Audubon’s work is sustenance for the soul. But first you have to know you have one.

[The author would like to thank James Kuslan, the author’s brother, for his eleemosynary perspicacity during the fashioning of this essay.]

[1] https://www.hmns.org/exhibits/audubons-birds-of-america/

[2] 75 by my count. The museum website specifies 46.

[3] Audubon’s sons sold many of his watercolors after his death to the New York Historical Society in 1863 https://www.audubonart.com/investigating-audubons-50-best-watercolors/

[4] https://www.audubongalleries.com/guide.php

[5] https://friendsofaudubon.org/the-double-elephant-folio-where-did-it-come-from/

[6] Edinburgh Evening Current, Nov. 6, 1826, in Chalmers, John, Audubon in Edinburgh and His Scottish Associates (Edinburgh, 2003), p. 40.

[7] The Journal of Walter Scott (NY, 1890). https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/14860/pg14860.txt

[8] Bennett, John Hughes, Memoirs of the Late Sir Robert Forbes (Edinburgh, 1855), p. 15. https://ia600806.us.archive.org/32/items/b30562065/b30562065.pdf

[9] Even skeptics like Hume would write, “[The] idea of God, as meaning an infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being, arises from reflecting on the operations of our own mind, and augmenting, without limit, those qualities of goodness and wisdom” (EU, 2.6/19; and cp. TA, 26/656; EU, 7.25/72) See https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hume-religion/ for the expanded bibliographic reference.

[10] Scruton, Roger, Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey (NY, 2012), p.12

[11] Audubon, John James, Ornithological Biography (Edinburgh, 1831), pgs. 438-40. https://archive.org/details/b22011535_0001/page/438/mode/2up

[12] Grosart, Alexander, Memoir and Remains of Alexander Wilson, The American Ornithologist (Paisley, 1876), p. 218, citing, Ord, George, American Ornithology ' (1814) Vol. VIII, pp. iii.- vii. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=mzppAAAAcAAJ&pg=GBS.PR16

[13] Chalmers, John, Audubon in Edinburgh and His Scottish Associates (Edinburgh, 2003), p. 141.

[14] The Autobiography of Charles Darwin (Collins, 1958), p. 51, in Chalmers, John, op. cit, p. 136.

[15] Chalmers, John, op. cit, p. 151.

[16] “Noctes Amrosianae (Christopher North, pseudonym of John Wilson), Blackwoods Magazine (1827), 21:105, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106019922548&seq=7

[17] https://www.debt.org/bankruptcy/statistics/

[18] https://www.rib.uscourts.gov/newhome/docs/the_evelution_of_bankruptcy_law.pdf

[19] “Mr. Audubon’s Account of his Method of Drawing Birds”, Edinburgh Journal of Science, Vol VIII, No. I, January 1828.

[20] Chalmers, John, op. cit, p. 30.

[21] Perhaps Mr. Logan’s book contains proof, but his film interview, as chosen by the curators for this film, does not reveal it. Neither does the polemical essay by an Audubon biographer found here: https://www.audubon.org/news/the-myth-john-james-audubon Elsewhere on its site, the Audubon Society washes its dirty linen in public with its own mea non culpa, Audubon culpa.

[22] “Chiliasm (pronounced ‘kiliasm’) is the ancient name for what today is known as premillennialism, the belief that when Jesus Christ returns he will not execute the last judgment at once, but will first set up on earth a temporary kingdom, where resurrected saints will rule with him over non-resurrected subjects for a thousand years of peace and righteousness.” https://www.modernreformation.org/resources/articles/why-the-early-church-finally-rejected-premillennialism

75 by my count. The museum website specifies 46.

Audubon’s sons sold many of his watercolors after his death to the New York Historical Society in 1863 https://www.audubonart.com/investigating-audubons-50-best-watercolors/

Edinburgh Evening Current, Nov. 6, 1826, in Chalmers, John, Audubon in Edinburgh and His Scottish Associates (Edinburgh, 2003), p. 40.

The Journal of Walter Scott (NY, 1890). https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/14860/pg14860.txt

Bennett, John Hughes, Memoirs of the Late Sir Robert Forbes (Edinburgh, 1855), p. 15. https://ia600806.us.archive.org/32/items/b30562065/b30562065.pdf

Even skeptics like Hume would write, “[The] idea of God, as meaning an infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being, arises from reflecting on the operations of our own mind, and augmenting, without limit, those qualities of goodness and wisdom” (EU, 2.6/19; and cp. TA, 26/656; EU, 7.25/72) See https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hume-religion/ for the expanded bibliographic reference.

Scruton, Roger, Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey (NY, 2012), p.12

Audubon, John James, Ornithological Biography (Edinburgh, 1831), pgs. 438-40. https://archive.org/details/b22011535_0001/page/438/mode/2up

Grosart, Alexander, Memoir and Remains of Alexander Wilson, The American Ornithologist (Paisley, 1876), p. 218, citing, Ord, George, American Ornithology ' (1814) Vol. VIII, pp. iii.- vii. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=mzppAAAAcAAJ&pg=GBS.PR16

Chalmers, John, Audubon in Edinburgh and His Scottish Associates (Edinburgh, 2003), p. 141.

The Autobiography of Charles Darwin (Collins, 1958), p. 51, in Chalmers, John, op. cit, p. 136.

Chalmers, John, op. cit, p. 151.

“Noctes Amrosianae (Christopher North, pseudonym of John Wilson), Blackwoods Magazine (1827), 21:105, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106019922548&seq=7

“Mr. Audubon’s Account of his Method of Drawing Birds”, Edinburgh Journal of Science, Vol VIII, No. I, January 1828.

Chalmers, John, op. cit, p. 30.

Perhaps Mr. Logan’s book contains proof, but his film interview, as chosen by the curators for this film, does not reveal it. Neither does the polemical essay by an Audubon biographer found here: https://www.audubon.org/news/the-myth-john-james-audubon Elsewhere on its site, the Audubon Society washes its dirty linen in public with its own mea non culpa, Audubon culpa.

“Chiliasm (pronounced ‘kiliasm’) is the ancient name for what today is known as premillennialism, the belief that when Jesus Christ returns he will not execute the last judgment at once, but will first set up on earth a temporary kingdom, where resurrected saints will rule with him over non-resurrected subjects for a thousand years of peace and righteousness.” https://www.modernreformation.org/resources/articles/why-the-early-church-finally-rejected-premillennialism

Superbly reasoned and written. Westerners who side with those who reflexively denigrate the noblest aspirations of their culture seem not to realize they are well on the way to committing suicide. Go right ahead but leave the rest of us far from your insane impulsions.