Pre-WWII English Authors (I)

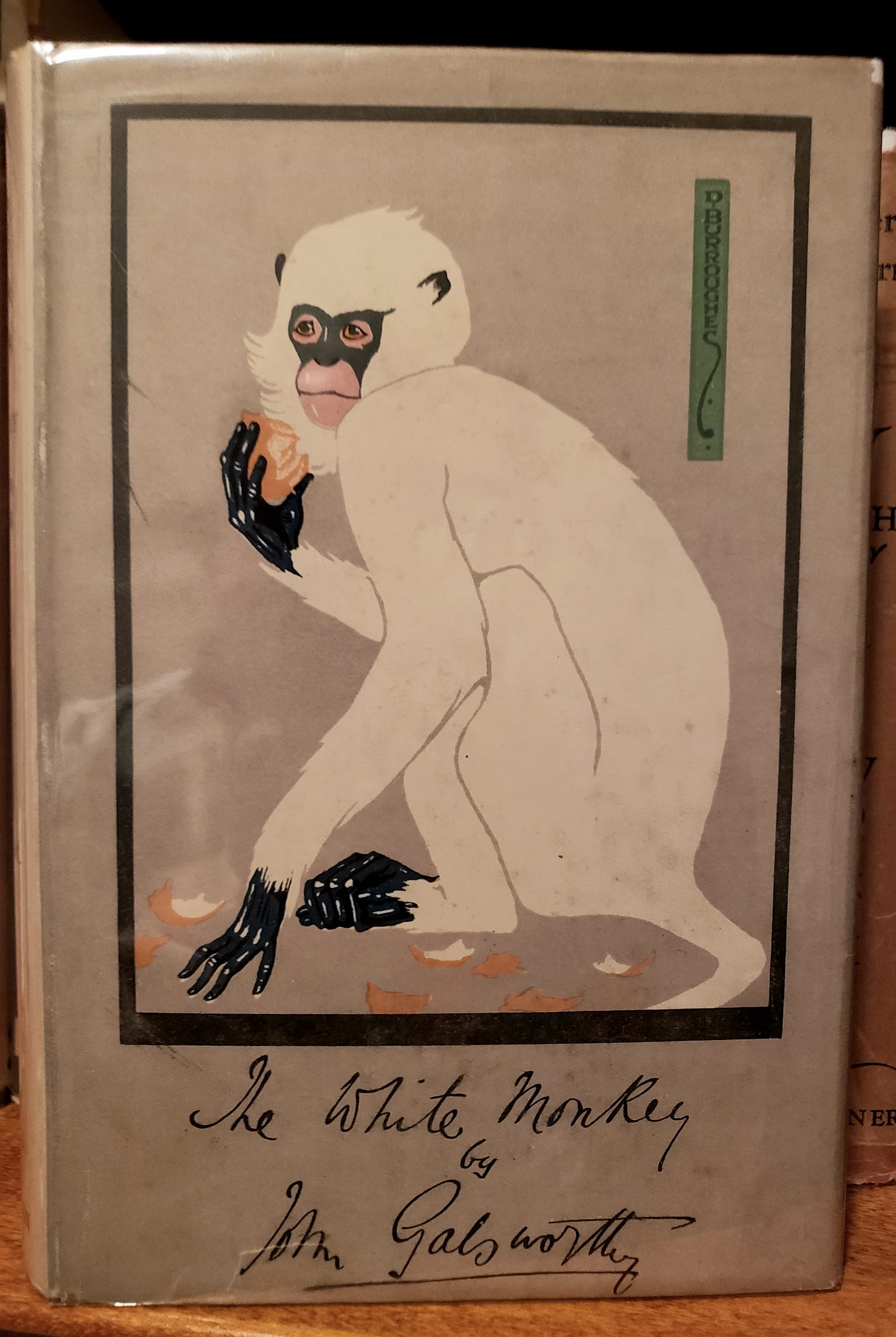

In 2022, I stumbled upon a copy of John Galsworthy’s, The White Monkey (1924) in mint condition with dust jacket for the price of a burger and fries.

The book dealer had perhaps thought Galsworthy unsaleable. Certainly, Galsworthy does not command the prices he once did more than 50 years ago. The gorgeousness of this copy appealed immediately to me. Few seem to read him any longer and I had never! I skimmed it, wondering if I ought to buy to resell — the other books I was to buy would then be gravy.

But, as is often the case with prose masters, his opening captured my attention and the first chapter held it.

Coming down the steps of 'Snooks' Club, so nicknamed by George Forsyte in the late eighties, on that momentous mid-October afternoon of 1922, Sir Lawrence Mont, ninth baronet, set his fine nose towards the east wind, and moved his thin legs with speed. Political by birth rather than by nature, he reviewed the revolution which had restored his Party to power with a detachment not devoid of humour. Passing the Remove Club, he thought: 'Some sweating into shoes, there! No more confectioned dishes. A woodcock--without trimmings, for a change!'

Vim and vigor pulses through this fine paragraph, much as Mont himself is made to move — and I liked Mont from the get-go with his “fine nose” and “thin legs” apace.

Of course, I bought the book, but to read and, I hoped, to savor. I think it was by the third chapter that I realized that, in my hands, I held a real gem of book collecting. It was a nearly perfect copy — dots of minor foxing, tight hinges, corners unbumped and cleanly white throughout — which I could enjoy just for the touch of its rag paper and cloth binding and for the sheer delight of reading for my own edification.

Not since Trollope had I read eccentric, yet round characters treated with as much loving compassion in a form mastered with such subtlety as to be transparent. I felt impelled, as if something within me set about to the chasing of a golden horn, to read all of his writing — voluminous as it is — over the next few years. I had done this with Dickens 40 years ago and Trollope, 20, and many other authors, but I never had thought that English fiction writers of the 1920s would prove such a boon.

I’ve since read The Man of Property (1906), written when he was still a young man and before the shock of the first war crushed many literary presumptions. That title, his first big seller — not self-published as were his first few works — proved a clumsy handling of plot with a pall cast prejudicially at his own creations. He had put his thumb on the scale.

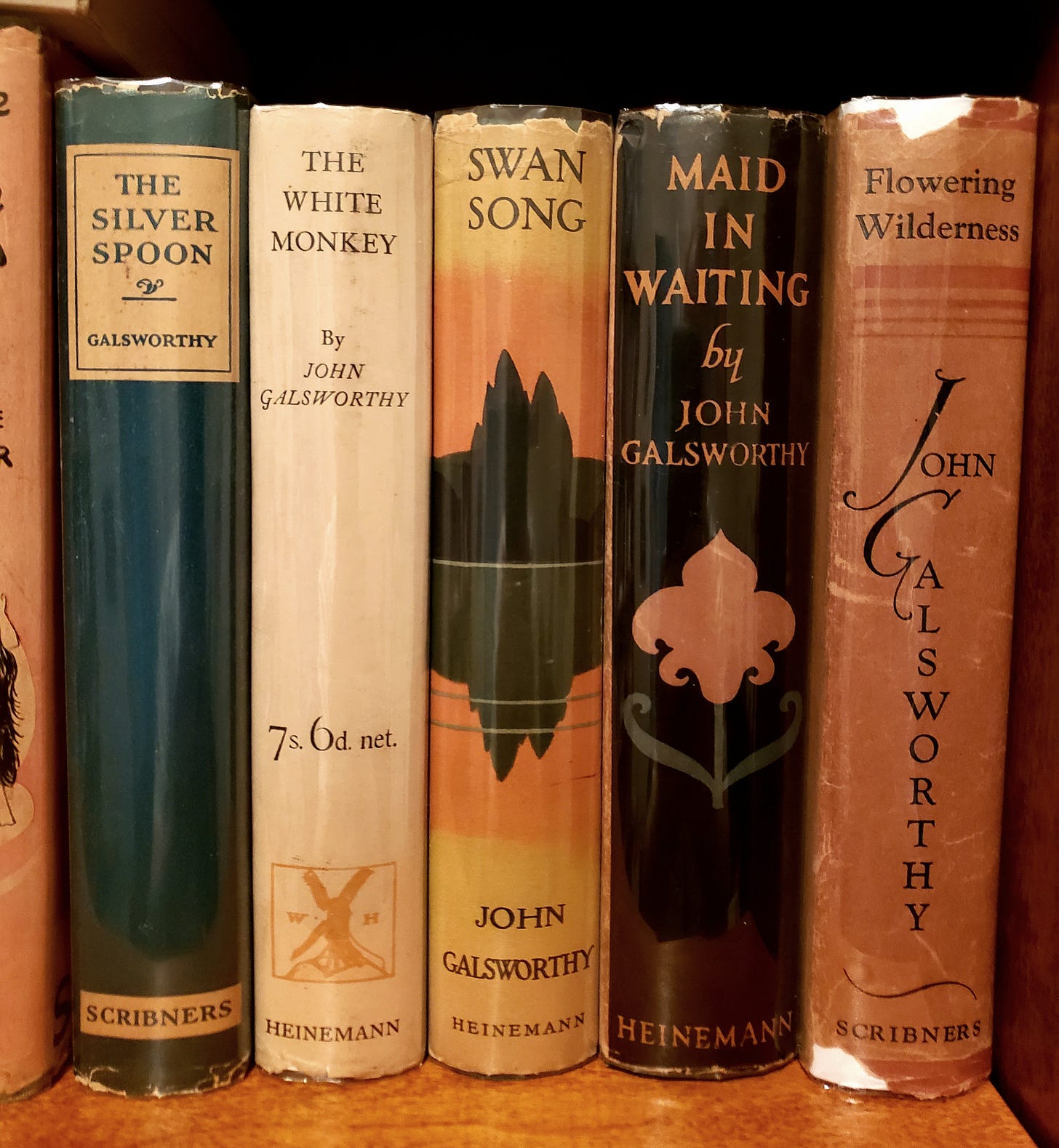

Later, his writing, to which The White Monkey had gratefully introduced me — I would have read no other Galsworthy writing had I started with The Man of Property — became populated with fictional creations he plainly loved (as God loves Man) and whom he deftly and deferentially treated with a master writer’s humane sense of fair play and justice. As for example in Silver Spoon (1926), Swan Song (1929), Maid in Waiting (1931) and Flowering Wilderness (1932).

The writing of his later life blossomed, most likely with the flowering of his own animate spirit, because one’s writing is either delimited or set free by one’s own inner attainment. It is as if the author’s youthful impetuosity had entirely gone and with it the immature imperative to prove a point by loading the dice against enemies; aged, he reveals a maturity that he had come to his conclusions of which he need not labor to persuade a soul; that things were just as they are; but one ought to look upon them with a mercy that the reader, who is a voluntary recipient who ought not to be compelled, might take it as he pleases. In addition, there is the almost Tennysonian quality of the language, rich in melody and sonorous harmonies. Swan Song moved me to tears by its pathetic and often plangent beauty, its exaltations, which can only come through a great master and artist.

Galsworthy has led me to other British writers of that period, including Henry Williamson, whose work will be the subject of my next post.