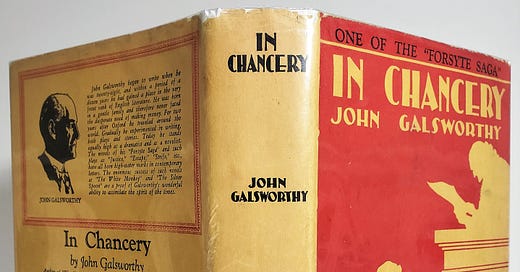

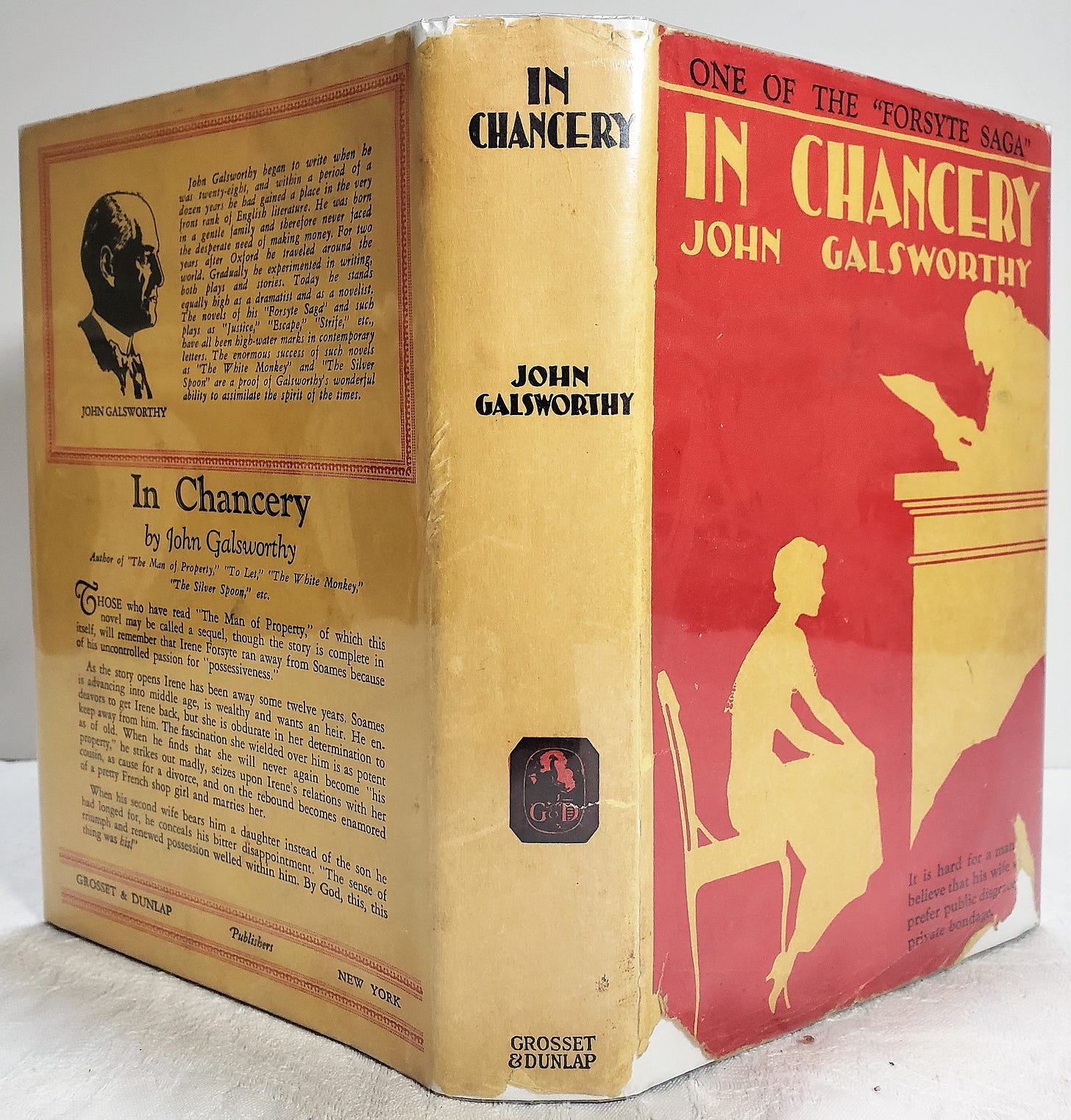

John Galsworthy, In Chancery (1920)

With every novel he wrote, Galsworthy became ever more compassionate towards his characters, whom he once set up inimically. The inner life, of which no man’s family or compatriots or friends or enemies might ever know, becomes the rich stuff of the loving author’s clay. Even “the man of property,” Soames Forsyte himself, a seemingly unfeeling stoic, is shown to suffer within himself a kind of misery by a thousand cuts which none but the author and his readers — certainly not the other characters — will ever know. A book of the deepest secrets that elicited from me both tears and laughter.

I picked up an American first edition in fairly nice shape with this superb period dust jacket. This one is a keeper. I’m sure I will read it again.

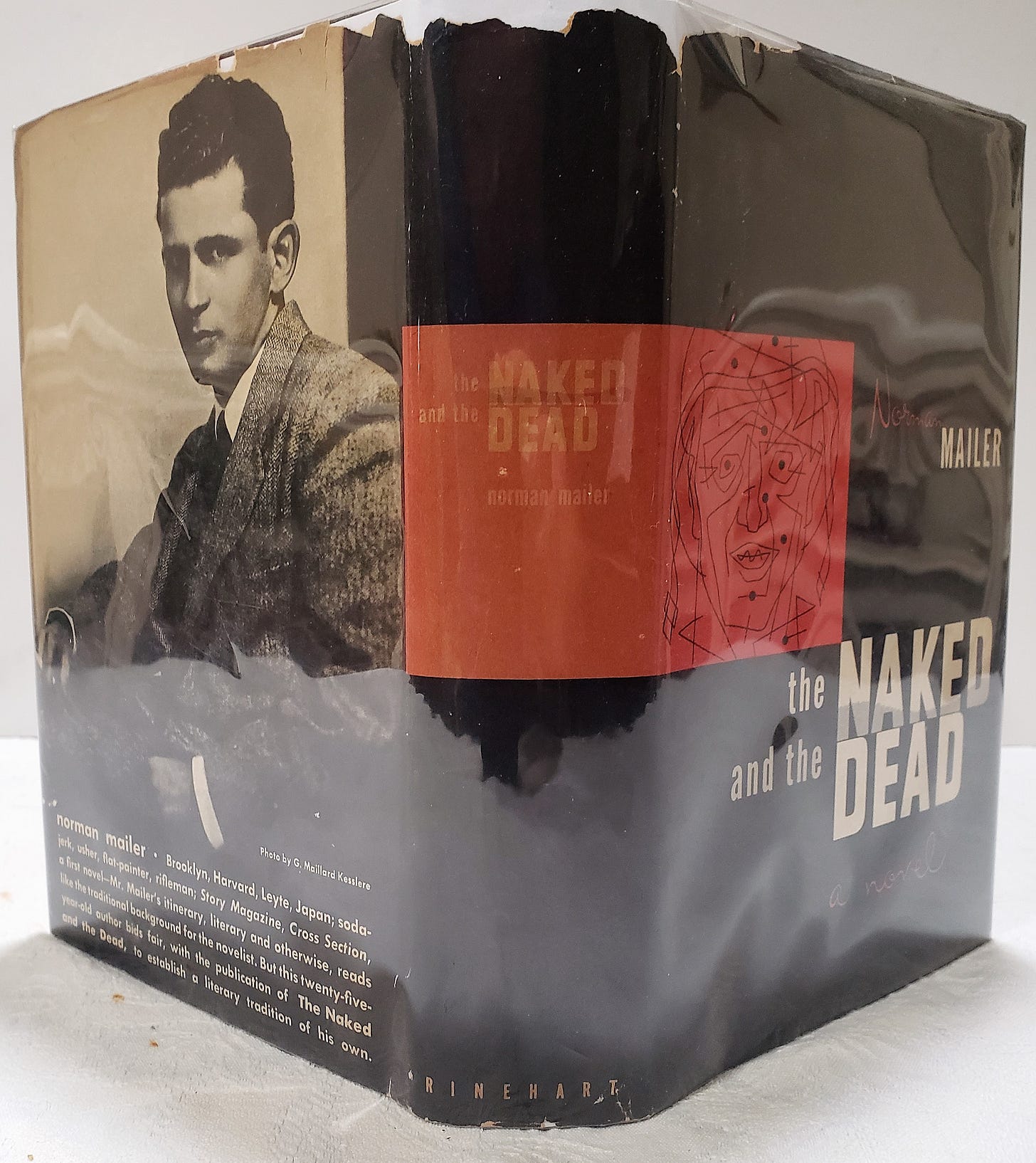

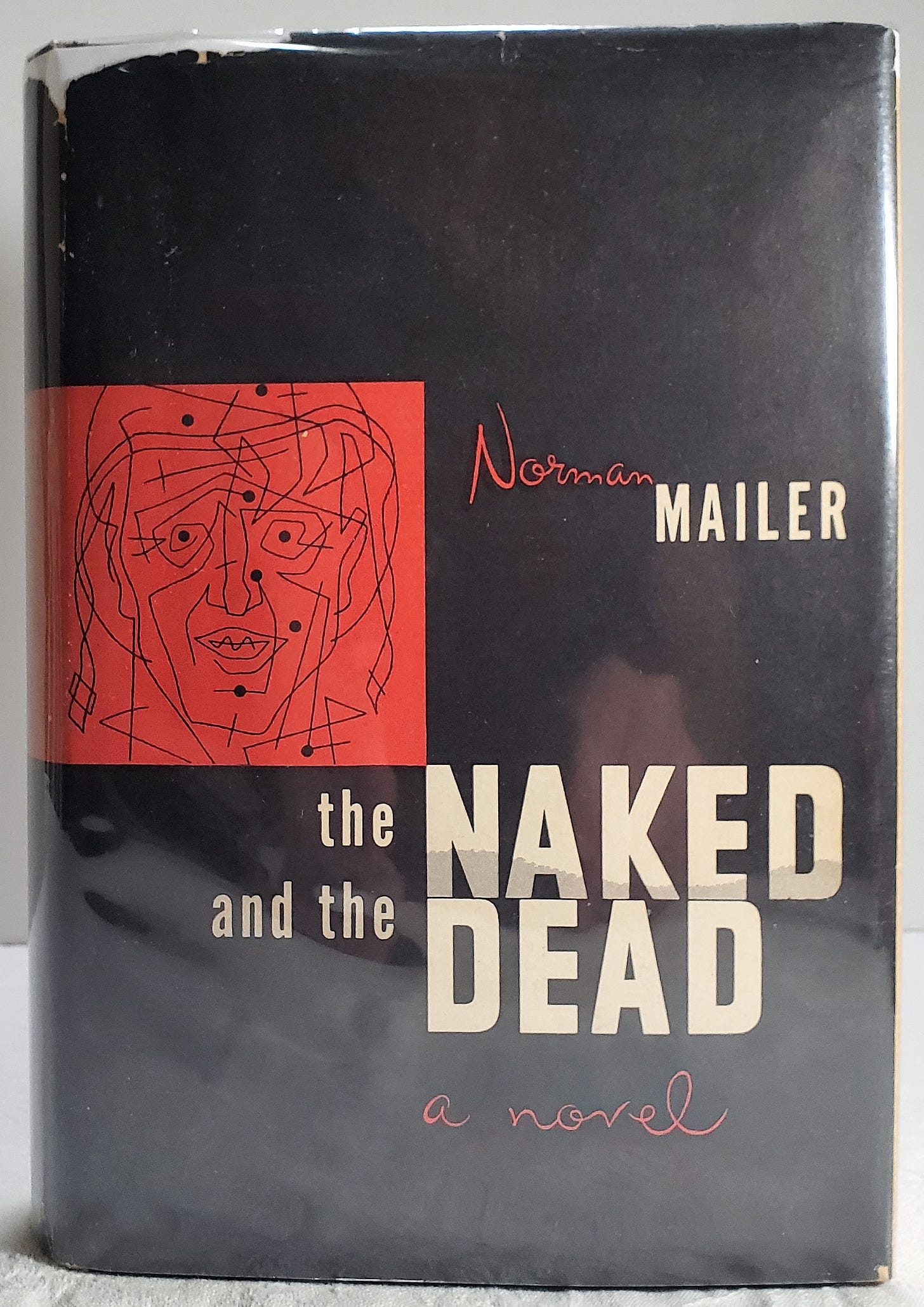

Norman Mailer, The Naked and the Dead (1948)

Prose so lifeless that even the first chapter was rough-going. Here’s an example:

“An ammunition dump began to burn, spreading a rose-colored flush over a portion of the beach. When several shells landed in its midst, the flames sprouted fantastically high, and soared away in angry brown clouds of smoke. The shells continued to raze the beach and began to shift inland. The firing had eased already into a steady, almost casual, pattern.” p.19

Where is the sound? What of the panic heartbeat a battle induces? What of the skin bubbling heat? Mailer wrote of what must be felt intensely, of life-altering experiences, with such cold detachment that I find his prose unpersuasive.

Why not something like this?

In less than the split-second it took for the heart to throb again, the orange-rose flash in the midst of the ammo dump suddenly thumped against the skin, knocking the observer backwards a pace; and then more shells landed, popping flames higher than the palm trees they burnt to a cinder in a brown, acrid smoke. Tommy guns cackled, their shrapnel searching for men to kill.

Now, I wrote the latter paragraph in three minutes, which I find far more evocative than Mailer’s prose. But this was an enormous seller at the time — lots of men back from the war obviously the intended readership. And yet, for all of its seemingly accurate G.I. dialogue and observation, it’s a curiously inert novel.

This copy is a first edition in a dust jacket at a reasonable price, but this is one I am certainly going to sell.

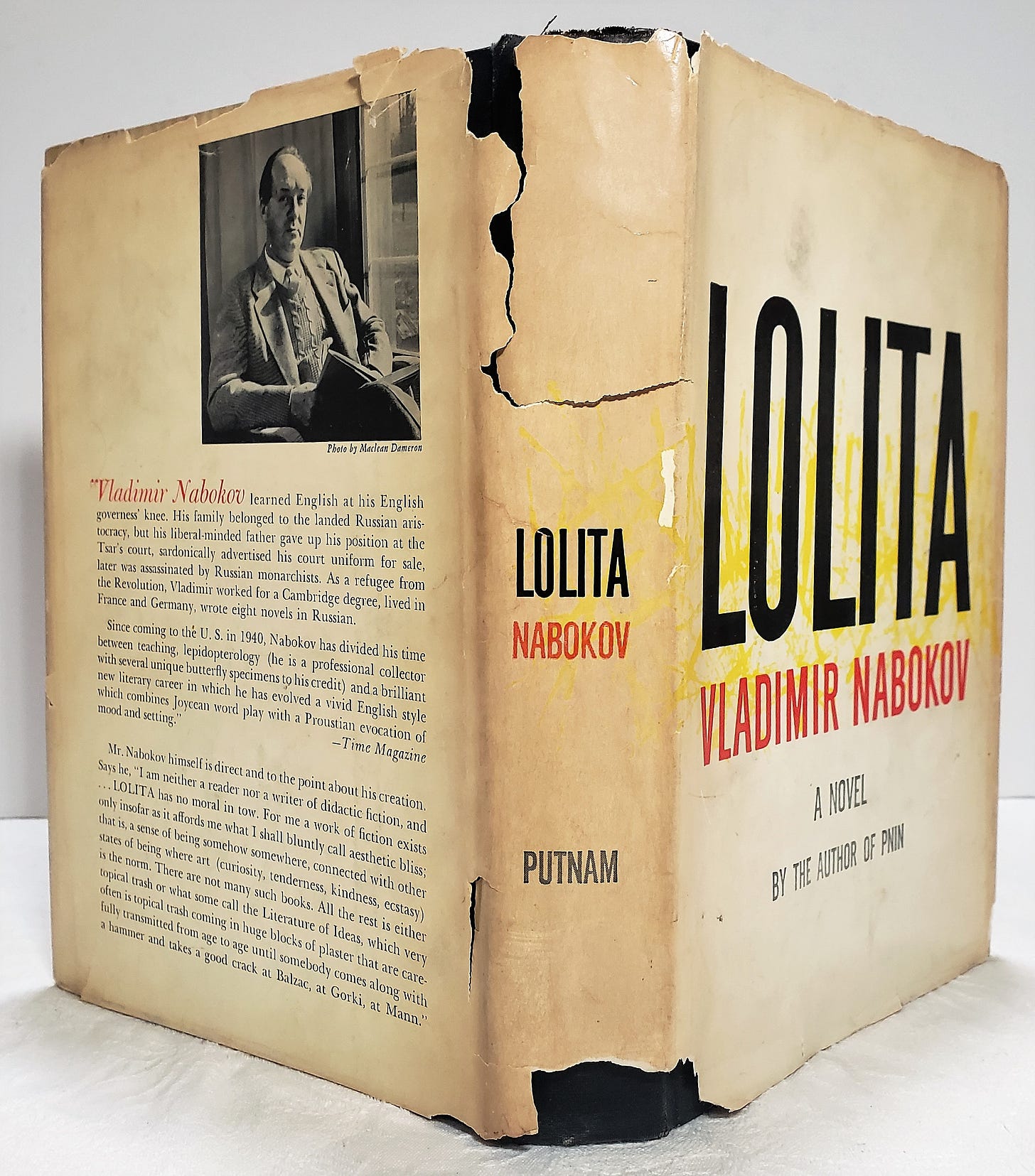

Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (1955)

Here is a novel that initially no American publisher would take on until after it had been first published in 1955 by the Olympia Press in Paris.

In the after-word, Nabokov wrote:

The four American publishers, W, X, Y, Z, who in turn were offered the typescript and had their readers glance at it, were shocked by Lolita to a degree that even my wary old friend F.P. had not expected…Their refusal to buy the book was based not on my treatment of the theme but on the theme itself, for there are at least three themes which are utterly taboo as far as most American publishers are concerned. The two others are: a Negro-White marriage which is a complete and glorious success resulting in lots of children and grandchildren; an the total atheist who lives a happy and useful life, and dies in his sleep at the age of 106.

To paint those who would not publish a book of fiction — whose story features an adult male who sexually terrorizes a pre-teenage girl of whom he is supposed to be the parental guardian — as also being Bible thumpers preternaturally opposed to miscegenation seems to me to be a rather low blow engendered by sour grapes, even if it were true. Or perhaps they just didn’t “get” the book.

In contradistinction to Galsworthy and Dickens, who love their characters and let them develop in the author’s loving guidance, Nabokov considered his characters his “galley slaves.” Was this because Humbert Humbert, the character whose own narration forms the substance of the novel, “is a vain and cruel wretch who manages to appear ‘touching?’” Can one write sympathetically or empathetically about so loathsome a character?

I don’t think one can. The revulsion towards a fictional character of this ilk can not overcome by any amount of authorial compassion and be truthful at the same time. Indeed, if, as Martin Amis proposed, Lolita is a critique of tyranny, deceit and abuse, then no amount of compassion will get the point across.

This is perhaps what the publishers missed. 1950s America, even though their men had come back from a war to destroy a perverse tyranny, went on blissfully unaware that personality traits similar to those which infested the leadership of the Stalinists, reside in the hearts of men who walk about freely on the streets of our country who would be cruel despots, if only they could do so with impunity.

Nabokov’s prose is deft, nimble and often exquisite, like a fine porcelain Capo di Monte.

My copy is a first American edition with dust jacket that has come down in the family since it was first purchased in a Manhattan bookshop upon its publication.