Frying Pan Writing and Savonarola

Finding expertly crafted English where one ought is still a delight

WRITERS MUST BE THE CUSTODIANS OF OUR PATRIMONY

Forty years ago, I wrote instruction manuals and marketing copy in English for a Japanese equipment maker. The Japanese comprehension of English, at the time, was studied, but unsubtle, even that of fluent speakers, and even for those few highly-trained specialists who became diplomats and NHK World News anchors.

A simultaneous translator, whose facility seems facile enough, is actually a species of genius born, not created. No amount of study will make a professional linguist into a simultrans, who exceed in accuracy and meaningfulness all machine attempts and at the speed of human speech. But these are rare beings. Just about everyone else struggles to some degree with translation.

Translation, as George Steiner once wrote, is interpretation. My writing, already demonstrating clarity and economy at that young age, required discussion with my Japanese employers, who often saw things differently; usually, wrongly. When persuasion failed, I finally let my immediate boss submit an entire manual in his English writing, over-riding my many red-pennings of his hard-fought sloggings with dictionary in hand, to the US branch.

He was, at times, a nice man, but where language is concerned, language came first. I understood this imperative at the core of my soul, even as a novice in the world of men and even if an attempt to safeguard language imperiled my employment. For we are custodians of the great language we have been entrusted to pass down to our descendants.

The US branch replied by telex, the machines by which we used to communicate internationally, with an excoriation that must have shamed my boss before his own manager. I heard the roof pop off, a good deal of yelling (in East Osaka, a factory town, men were boisterous) and I remember people running around.

The manual had been rife with laugh-making gaffes - a waste of company time to create it and review it. I recall his accusatory claim that followed, to which I responded, that I told you what was wrong and what to do about it. “But you approved it!” he answered. Ah, so, but you are my Kakari-cho (係長: an assistant manager), and I had to. Thereafter, English was English.

DON’T YOU EVER TALK TO ME THAT WAY AGAIN!

At least, until I was fired several months later. The Number 2 guy in the company, who actually ran operations while the big boss (社長) was practicing his calligraphy in the penthouse, was widely hated: a tyrant with a gloomy, smug haughtiness, even as he sucked up obsequiously to Number 1. I had had little communication with either until a medical incident sent me from the office by ambulance to the emergency room. In recovery, I roomed with my first thoroughly tattoo’d, forefinger cut off at the knuckle, Yakuza underboss friend — oh my gosh, he loved me — who was dying of cirrhosis.

Upon my return, Number 2 publicly insulted me with a smirk, claiming that I had feigned illness. My outburst in response was of such sudden outrage to have frightened even this bully. He ran from me. I followed. Fortunately, in that office, I had a fatherly protector in his 50s, a consummate professional, courteous, intelligent and subtle. He effortlessly stepped in front of me and stopped my advance with a light touch on my chest. Of course, those wise blue-grey eyes of his convinced me right away of the necessity to cool down.

Hayano-san (早野様)became a model for me then, as someone always too ready for a joust with any man. To this day I have been unable to find him, even through friends still living in Osaka, though I remember his name and where he lived, to thank him for his love and attention. If he is even still alive. He would be over 90, but Japanese men live long lives.

On my last day, which was that day, the girls on the first floor, who worked directly under Number 2, got together out of sight of him, to shout 「リッチ様、偉い!」”Richie-san is great!” and bowed with gratitude, for I had taken the wolf down a peg. I distinctly recall the prettiest of them giving me a quick, light kiss on the cheek and running back behind her desk, as they all chirped with joy. I have somewhere out in the garage the note of thanks they all signed.

To this day, just as I disdain inaccurate and clumsy misuse and abuse of language — there is so much of it, especially galling when the adult writer has gone to graduate school and still writes like he never finished junior high — I admire correct and deft application of language wherever I see it.

HISTORICAL WRITING AND THE FRYING PAN

One surely ought to be able to expect writing of professional historians to be, at a minimum, grammatical, syntactically precise and well-suited to purpose and meaning, and illuminating. Very sadly, so much of what is published today, often with university imprimatur, is execrable English.

There is a vast trove of contemporary historical writing in English that could be significantly improved, if only a real editor had gotten at it to cut the fat, shape the ideas into manageable sections and carry the reader from cover to cover with a style that eases the reader through the evidence offered in support of the author’s propositions. Quite often, I have read books by even well-known academic authors with obviously superior command over subject matter that read like drafts.

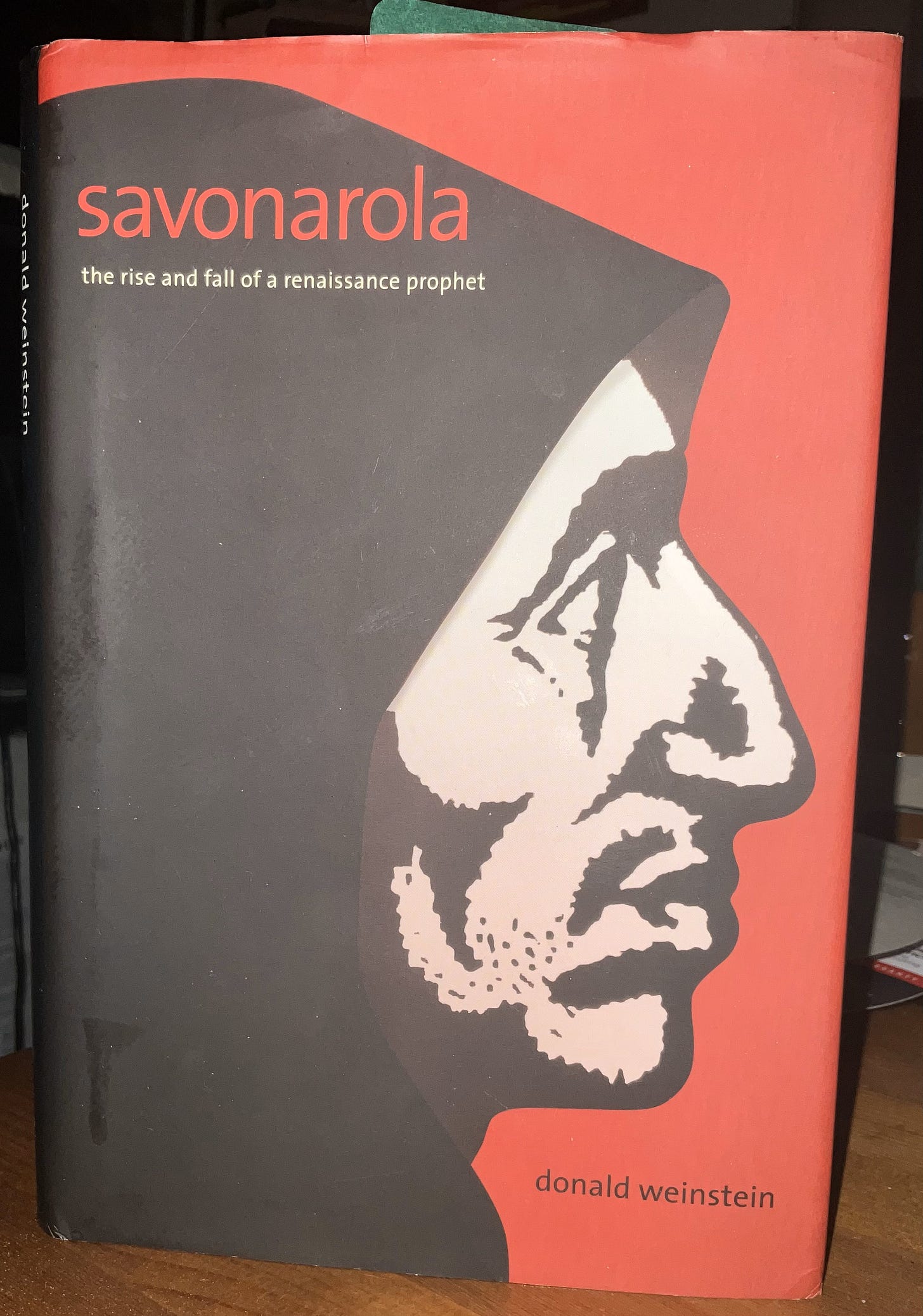

I was surprised and delighted to read Donald Weinstein’s Savonarola: The Rise and Fall of a Renaissance Prophet. (I picked up a mint used copy for $25.) An example:

"Tell your thoughts to few because everyone will be your enemy," he had written three years earlier in On the Ruin of the World, and in this new poem, although intimating that the Church will suffer divine retribution for its sins, he concludes that mortal speech can do nothing. "Weep and be silent, this seems best to me." If his superiors had any inkling of his criticism there is no sign. While most young friars received only two or three years of instruction in the Bologna studium before moving on to other teaching and preaching duties, the more intellectually promising were advanced to the higher course of theology in preparation for an academic career. Fra Girolamo was one of these select few. Since the San Domenico school was a studium generale, associated with the University of Bologna and authorized to grant the bachelor and master of sacred theology degrees, fra Girolamo would be able to pursue his studies without moving away from the mother convent. In his second year in the program, on July 3, 1478, he was designated studens formalis, signifying his matriculation in the theological faculty of the university, on course for a higher degree. Among the teachers at the studium were Pietro da Bergamo, compiler of a comprehensive guide to the works of Saint Thomas Aquinas; Nicolò da Pisa, who was to become known for his writings on asceticism; and Vincenzo Bandelli, in the early stages of his own important career as theologian, professor, and, ultimately, general of the Order. Whatever Girolamo's reservations about scholastic disputations and overemphasis on Aristotelian logic, he would participate in weekly disputations and teach the logic, ethics, and philosophy of "the Philosopher" to beginning students as well as attend lectures in theology and Bible. [Footnotes removed.]

The author devotes one paragraph to one idea (Savonarola’s training as a novice Domincan friar); one sentence, to one idea, each building upon the next to support the meaning of the whole while illuminating his subject’s character. His sentences are models of clarity and ease of style. The writer possesses a mastery of the subject matter. Even someone like me, who has never read in 15th century Italian religious polity, can readily swim buoyed by such writing in this deep sea of obscure knowledge.

This is precisely the quality of writing the colleges used to train promising young thinkers to achieve. Donald Weinstein was trained in — and thereafter trained himself, as every capable writer must do — that now centuries-old tradition predating even Gibbon: The tradition of objective historicism, the goal of which is the discovery of the truth of the matter studied, which requires a mastery of written English to communicate cogently and succinctly. [If you’ve never read it, Gibbon’s awe-inspiring, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is so good, I’ve read it three times, cover to cover, in my life and will read it again in future.]

NOW FOR THE FRYING PAN

We bought a non-stick T-FAL frying pan for the house. It is an excellent pan. To make sure I didn’t damage it, my lovely wife insisted I read the instructions. I read them this morning to my great delight, because I found them exceedingly well-written.

CLEANING

Cleaning your T-fal non-stick cookware is wonderfully easy: wash in warm soapy water using a cloth, sponge or non-abrasive scouring pad. Never use abrasive cleaners or scouring pads, such as steel wool or scouring powder. T-fal cookware with enamel or non-stick exteriors can also be cleaned in a dishwasher, but please be aware that the glossy porcelain enamel finish may discolour and become dull after a while due to the abrasive nature of dishwasher detergents. These effects are not covered under the warranty. When placing non-stick cookware in a dishwasher take extra care to place the items as vertically as possible between the spikes of the rack in order to minimize friction between the non-stick surface and the spikes during the washing cycle. We recommend re-seasoning the pans with a little cooking oil after every 10 dishwashing cycles. Note: We recommend not to put T-fal cookware with polished or brushed aluminum exteriors in the dishwasher to avoid discolouration.

Two colons, both used properly! That is, general: specific. X:Y, where X introduces the topic which Y explains and clarifies. Syntax, grammar, style — all very satisfactory to the eye. After hundreds of Chinese-written mash-ups of instruction manuals (Americans don’t do much better), this writing, discovered on a throw-away cardboard, was a sheer delight for me.

My guess is that the writer is female (“wonderfully easy”), English (or studied literature at an English university) with a degree in French; and a fiction writer by trade, who loves to cook, and who has picked up a side gig, as so many writers must, translating and re-writing in cogent, effortless English. Now I want to read this person’s own writing! Who is the author?

What the writer has done, in a most praiseworthy way, is to pass on the greatest, that is, the patrimony of English writing which all of us have (or ought to have) gratefully inherited, by means of the littlest; in every detail, everything one writes for another reader, writers of the English language have a duty, owed both to the dead who created it, and to our descendants, who will pass it on, to uphold, nurture, develop, encourage and, most importantly, to exemplify it.